Another month goes by, which means it’s time for another release!

ClickHouse version 25.11 contains 24 new features 🦃 27 performance optimizations ⌚ 97 bug fixes 🍄

This release introduces ACME (Let's Encrypt) integration, parallel merge for small GROUP BYs, projections as secondary indices, and more!

New contributors #

A special welcome to all the new contributors in 25.11! The growth of ClickHouse's community is humbling, and we are always grateful for the contributions that have made ClickHouse so popular.

Below are the names of the new contributors:

AbdAlRahman Gad, Aleksei Shadrunov, Alex Bakharew, Alex Shchetkov, Animesh, Animesh Bilthare, Antony Southworth, Cheuk Fung Keith (Chuck) Chow, Danylo Osipchuk, David K, John Zila, Josh, Julian Virguez, Kaviraj Kanagaraj, Ken LaPorte, Leo Qu, Lin Zhong, Manuel, Mohammad Lareb Zafar, Nihal Z. Miaji, NilSper, Nils Sperling, Saksham10-11, Saurav Tiwary, Sergey Lokhmatikov, Shreyas Ganesh, Spencer Torres, Tanin Na Nakorn, Taras Polishchuk, Todd Dawson, Zacharias Knudsen, Zicong Qu, luxczhang, r-a-sattarov, tiwarysaurav, tombo, wake-up-neo, zicongqu

Hint: if you’re curious how we generate this list… here.

You can also view the slides from the presentation.

ACME (Let's Encrypt) integration #

Contributed by Konstantin Bogdanov, Sergey Lokhmatikov #

ClickHouse 25.11 introduces the capability to provision and use TLS certificates automatically. The certificates are shared across the cluster using ClickHouse Keeper, and it integrates with Let’s Encrypt, ZeroSSL, and other providers.

An example configuration is shown below:

1# /etc/clickhouse-server/config.d/ssl.yaml

2http_port: 80

3acme:

4 email: feedback@clickhouse.com

5 terms_of_service_agreed: true

6 # zookeeper_path: '/clickhouse/acme' # by default

7 domains:

8 - domain: play.clickhouse.com

Parallel merge for small GROUP BY #

Contributed by Jianfei Hu #

“We optimize ClickHouse and then we optimize ClickHouse again and then we are not satsified, and optimize it again!” - Alexey Milovidov, creator of ClickHouse, in a recent release webinar

GROUP BY remains one of the most important relational operators in ClickHouse. It has the richest set of specializations, the widest variety of algorithms, and receives continuous performance improvements.

After recently reducing memory and CPU usage for GROUP BY with simple count() aggregations, this release brings another boost: faster GROUP BY operations on small 8-bit and 16-bit integer keys. We achieve this by parallelizing the merge step for one of the specialized aggregation structures.

(This optimization naturally benefits a narrower slice of queries, but at ClickHouse, we pursue every opportunity to make queries faster, whether the gain is massive or highly specialized.)

Before demonstrating it with a concrete example, let's take a brief look under the hood of this optimization.

How GROUP BY runs in parallel today #

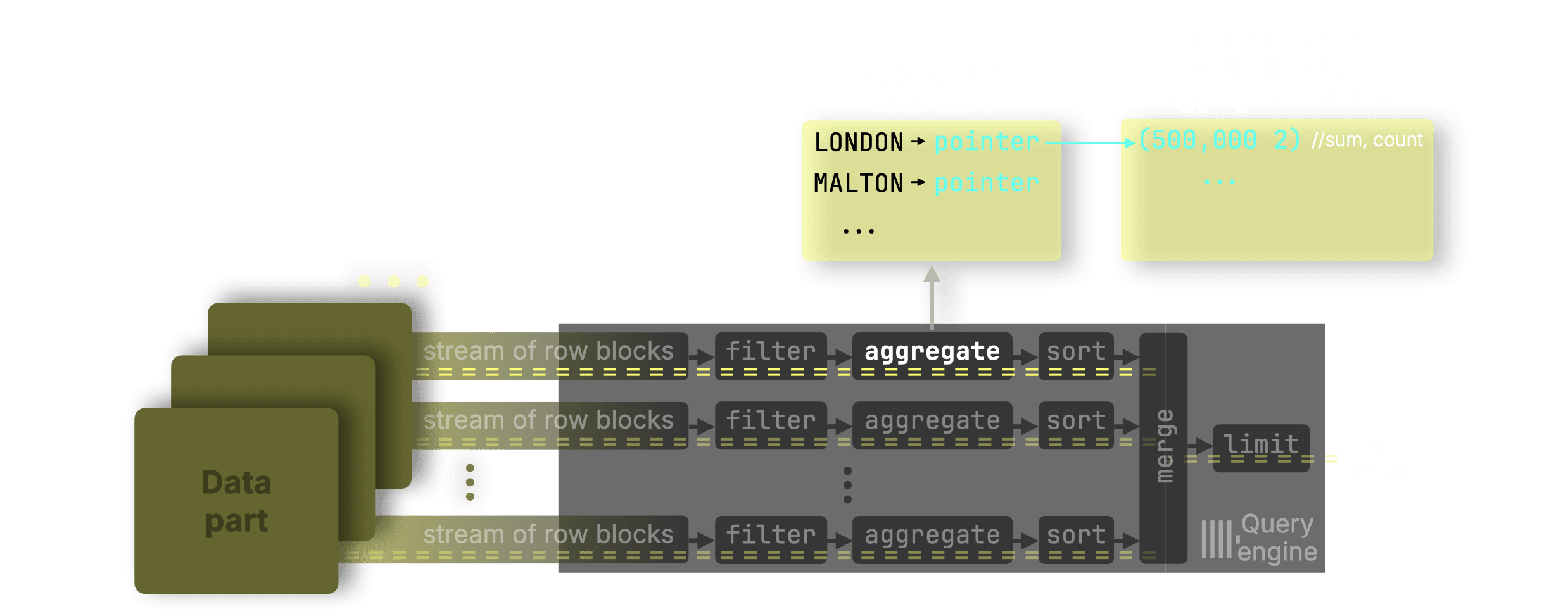

As already explained in a previous release post, ClickHouse runs GROUP BY highly parallelized across all CPU cores:

① Data is streamed into the engine block by block,

② each CPU core processes its own range (filtering, aggregating, sorting), and

③ the partial aggregation states from all streams are merged into the ④ final result.

Inside the aggregate step, ① each stream maintains its own hash table, mapping each key to a partial aggregation state. For example, avg() keeps a local sum and count per key. These partial states are then ② merged and ③ finalized:

In the general case, ClickHouse uses a two-level hash table, where keys point to aggregation states stored in a shared memory arena:

In the general case, the merge step itself (② in the animation above) is parallelized across multiple merge threads.

(Separately, if the query computes multiple aggregates, such as COUNT, SUM, or MAX, each aggregate maintains its own partial states, and their merges run in parallel with each other.)

But GROUP BY is heavily specialized #

ClickHouse does not use a single hash table implementation. It uses 30+ specialized variants, automatically selected depending on:

- key type,

- expected cardinality,

- aggregation functions used,

- and other query characteristics.

For example:

-

For

GROUP BY … count(), ClickHouse skips the memory arena entirely and stores counts directly inside the hash table cells. -

For queries grouping by small integer keys (8-bit, 16-bit), ClickHouse uses a highly optimized FixedHashMap, essentially an array indexed directly by the key value.

And this specialization is what matters here.

While the merge step is parallel for the general two-level hash table, until this release the merge step was single-threaded when the aggregation used FixedHashMap.

This meant that queries grouping on small integers (common in dimensional and categorical analytics) did not benefit from multi-threaded merging.

New in 25.11: Parallel merge for FixedHashMap #

ClickHouse 25.11 parallelizes the merge step for GROUP BY queries using small 8-bit and 16-bit keys. Each processing stream still builds its own FixedHashMap, but now the final merge can be performed by multiple threads working on disjoint regions of these maps.

Example: averaging price per property type #

Here’s an example using 8-bit keys: a query computing the average price per property type in the UK property prices dataset:

1SELECT 2 type, 3 avg(price) AS price_avg 4FROM uk_price_paid 5GROUP BY type

The type column is an Enum8 ('terraced' = 1, 'semi-detached' = 2, 'detached' = 3, 'flat' = 4, 'other' = 0) and is stored internally as an 8-bit integer.

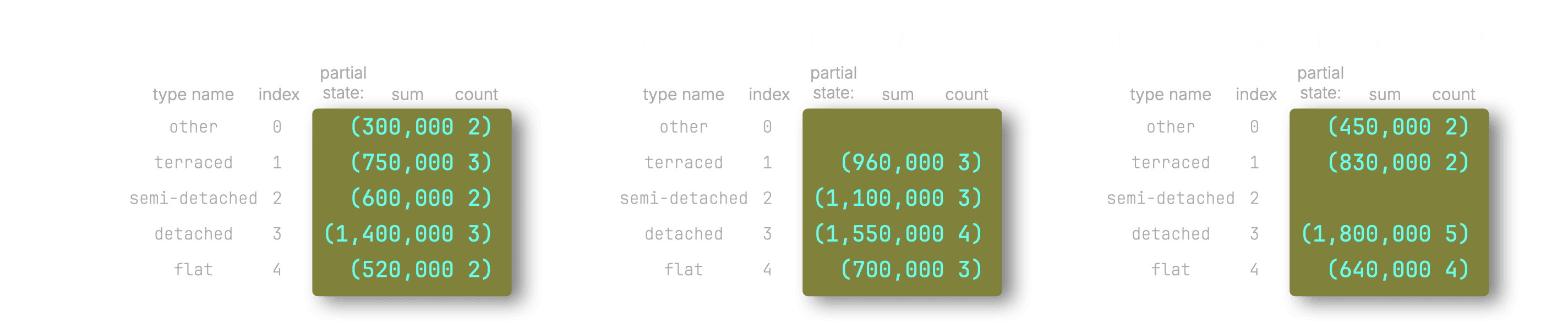

When running the query above, each processing stream stores partial states in a FixedHashMap, an array indexed directly by the key. This gives extremely fast inserts/lookups and, crucially, lets multiple merge threads operate safely on different key ranges without lock contention.

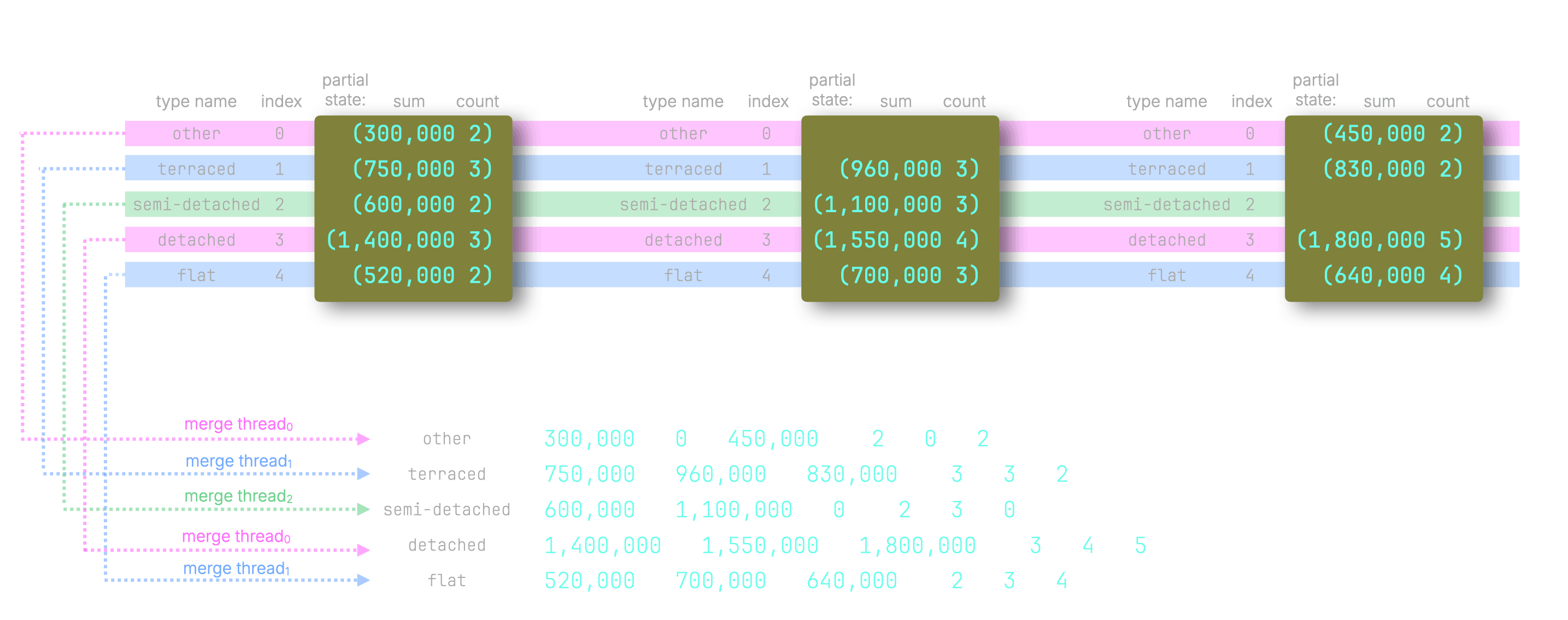

The three maps below show the partial avg states produced independently by three parallel streams (on a machine with three CPU cores).

ClickHouse then uses three parallel merge threads to combine these partial states. Each merge thread is assigned an ID (0–2) and processes only the positions corresponding to that ID. For example, thread 0 handles positions 0, 3, 6…, thread 1 handles 1, 4, 7…, and thread 2 handles 2, 5, 8….

The diagram illustrates how the three threads (sketched with three different colors) merge corresponding entries across maps:

In practice, all partial maps are merged into a single result FixedHashMap: the merge threads write the final averages for each key into that map, and the design allows them to work on different portions safely in parallel (ordinary hash tables cannot support this because they are not thread-safe for insertions).

Performance gains #

This optimization is most noticeable for aggregation functions that require non-trivial merge operations. In a typical GROUP BY query, the merge phase is only one part of the work, alongside reading data, computing expressions, and sorting. For trivial aggregations such as count, avg, max, or min, the merge step contributes very little to total query time. In contrast, aggregations with large partial states like uniqExact spend significantly more time merging, which is why they benefit most from this improvement.

To illustrate the effect clearly, we use uniqExact, whose partial states store raw distinct values (or their hashes, depending on the type) and merge them by distinct union.

We benchmarked this on an AWS m6i.8xlarge EC2 instance (32 cores, 128 GB RAM) with a gp3 EBS volume (16k IOPS, 1000 MiB/s max throughput), using the following query:

1SELECT 2 type, 3 uniqExact(street) AS u 4FROM uk.uk_price_paid 5GROUP BY type 6ORDER BY u ASC;

(You can create the table and load the data yourself using the instructions here.)

On 25.10, the fastest of three runs (with the OS page cache initially cleared) finished in 0.143 seconds:

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.159 sec. Processed 30.73 million rows, 100.09 MB (193.80 million rows/s., 631.22 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 153.28 MiB.

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.143 sec. Processed 30.73 million rows, 100.09 MB (214.45 million rows/s., 698.48 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 152.92 MiB.

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.148 sec. Processed 30.73 million rows, 100.09 MB (207.14 million rows/s., 674.66 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 154.35 MiB.

On 25.11, the fastest run completed in 0.089 seconds under the same conditions:

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.101 sec. Processed 30.73 million rows, 100.09 MB (302.84 million rows/s., 986.37 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 113.11 MiB.

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.089 sec. Processed 30.73 million rows, 100.09 MB (344.56 million rows/s., 1.12 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 112.69 MiB.

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.092 sec. Processed 30.73 million rows, 100.09 MB (335.41 million rows/s., 1.09 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 112.61 MiB.

The result: 0.089 s vs. 0.143 s — roughly a 40% speedup.

Additionally, if we run the query with trace logging enabled (SETTINGS send_logs_level = 'trace'), 25.11 clearly shows that the parallel merge path is being used:

...

AggregatingTransform: Use parallel merge for single level fixed hash map.

...

In short: every GROUP BY on small integer keys now benefits from a fully parallel merge path, unlocking additional speedups.

For a detailed engineering deep dive into how this optimization was implemented, see Parallelizing ClickHouse aggregation merge for fixed hash map.

Projections as secondary indices #

Contributed by Amos Bird #

Primary indexes are ClickHouse's most important mechanism for speeding up filtered queries. But because this index depends on the physical sort order of the table, each table can have only one primary index.

To accelerate queries whose filters don't align with that single index, ClickHouse offers projections - automatically maintained, hidden table copies stored in different sort orders. Since release 25.6, ClickHouse can create lightweight projections that behave like secondary indexes by storing only their sorting key plus a _part_offset pointer back to the base table, greatly reducing storage overhead.

Until now, this mechanism could only prune entire parts. With this release, _part_offset-based projections now support granule-level pruning, enabling much finer filtering and dramatically faster queries.

Results: On the UK price paid dataset with two lightweight projections (by_time and by_town), a query filtering on both date and town showed a 90% speedup (0.010s vs 0.077s), reading only ~16k rows instead of scanning all ~30 million rows. ClickHouse used the primary indexes of both projections as secondary indexes to prune base table granules.

Two new settings control this optimization:

max_projection_rows_to_use_projection_index: Maximum estimated rows to read from projection before applying its indexmin_table_rows_to_use_projection_index: Minimum estimated table rows before considering projection index

ClickHouse tables once had only one primary index. Now they can have many, each behaving like a primary index, and ClickHouse will use all of them when your query has multiple filters.

Read the full deep-dive on projections as secondary indices →

Speed up DISTINCT with projections #

Contributed by Nihal Z. Miaji #

This release includes a second projection-based optimization.

As described in the previous section, projections are automatically maintained, hidden table copies stored in a different sort order, or even in a pre-aggregated layout, to speed up queries that benefit from that data organization.

When a query runs, ClickHouse automatically chooses the cheapest data path, reading either from the base table or from a projection to minimize the amount of data scanned.

With this release, the same logic now accelerates DISTINCT queries as well: if retrieving all distinct values requires reading fewer rows from a projection, ClickHouse will automatically use it.

A common way to reduce the number of rows needed for a DISTINCT is to define a projection that pre-aggregates the data using a GROUP BY that includes the distinct key. Such a projection still contains every distinct value, but in far fewer rows than the base table, making it the clearly cheaper source.

To demonstrate this, once more, we use the UK price paid dataset, this time defining the table with a sales projection:

1CREATE TABLE uk.uk_price_paid_with_sales_proj

2(

3 price UInt32,

4 date Date,

5 postcode1 LowCardinality(String),

6 postcode2 LowCardinality(String),

7 type Enum8(

8 'terraced' = 1, 'semi-detached' = 2, 'detached' = 3, 'flat' = 4, 'other' = 0),

9 is_new UInt8,

10 duration Enum8('freehold' = 1, 'leasehold' = 2, 'unknown' = 0),

11 addr1 String,

12 addr2 String,

13 street LowCardinality(String),

14 locality LowCardinality(String),

15 town LowCardinality(String),

16 district LowCardinality(String),

17 county LowCardinality(String),

18 PROJECTION sales (

19 SELECT count(), sum(price), avg(price)

20 GROUP BY county, town, district

21 )

22)

23ENGINE = MergeTree

24ORDER BY (postcode1, postcode2, addr1, addr2);

Then we load the data using the instructions here.

This projection wasn’t created specifically for DISTINCT queries, that benefit is simply a nice side effect. Its primary purpose is to efficiently answer queries like identifying the top UK areas or the most lucrative regions.

For DISTINCT acceleration, the projection’s SELECT clause does not matter; what matters is that the distinct key appears somewhere in the projection’s GROUP BY.

Note that the GROUP BY keys need not be listed in the projection’s SELECT clause. They are implicitly part of the projection’s sorting key, with a primary index built on them for fast filtering, and queries can still select these columns when reading from the projection:

1SELECT

2 type,

3 sorting_key

4FROM system.projections

5WHERE (database = 'uk') AND (`table` = 'uk_price_paid_with_sales_proj') AND (name = 'sales');

┌─type──────┬─sorting_key──────────────────┐

1. │ Aggregate │ ['county','town','district'] │

└───────────┴──────────────────────────────┘

And with that, all distinct county, town, and district values are present in the projection tables, but in much fewer rows:

1SELECT sum(rows)

2FROM system.projection_parts

3WHERE (database = 'uk') AND (`table` = 'uk_price_paid_with_sales_proj') AND (name = 'sales') AND active;

┌─sum(rows)─┐

1. │ 9761 │

└───────────┘

Note that this row count decreases further as background part merges continue to incrementally apply the pre-aggregation.

The projection’s base table has over 30 million rows:

1SELECT count() from uk.uk_price_paid_with_sales_proj;

┌──count()─┐

1. │ 30729146 │ -- 30.73 million

└──────────┘

We benchmarked the queries below on an AWS m6i.8xlarge EC2 instance (32 cores, 128 GB RAM) with a gp3 EBS volume (16k IOPS, 1000 MiB/s max throughput).

We run a DISTINCT query on the town column over the base table by disabling projections:

1SELECT DISTINCT town

2FROM uk.uk_price_paid_with_sales_proj

3SETTINGS

4 optimize_use_projections = 0;

The fastest of three runs is 0.062 seconds:

1173 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.062 sec. Processed 30.73 million rows, 61.46 MB (494.48 million rows/s., 988.97 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 2.11 MiB.

1173 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.064 sec. Processed 30.73 million rows, 61.46 MB (483.01 million rows/s., 966.02 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 1.51 MiB.

1173 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.063 sec. Processed 30.73 million rows, 61.46 MB (487.14 million rows/s., 974.28 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 1.20 MiB.

Note that it was a full table scan reading all of base table’s ~30 million rows.

Now we run the same DISTINCT query with projections enabled:

1SELECT DISTINCT town

2FROM uk.uk_price_paid_with_sales_proj

3SETTINGS

4 optimize_use_projections = 1; -- the default value

1173 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.003 sec. Processed 9.76 thousand rows, 59.46 KB (3.29 million rows/s., 20.05 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 472.22 KiB.

1173 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.003 sec. Processed 9.76 thousand rows, 59.46 KB (3.29 million rows/s., 20.01 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 472.22 KiB.

1173 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.003 sec. Processed 9.76 thousand rows, 59.46 KB (3.37 million rows/s., 20.54 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 472.22 KiB.

The fastest of three runs is 0.003 seconds - roughly a 96% speedup.

This time, ClickHouse didn’t scan all 30 million rows of the base table to find the distinct towns. Instead, it chose to read only all 9.76 thousand projection table rows, because that path required far less data. That’s the magic of projections: ClickHouse simply picks the cheaper source.

argAndMin and argAndMax #

Contributed by AbdAlRahman Gad #

ClickHouse 25.11 introduces the argAndMax and argandMin functions. Let’s explore these functions using the UK property prices dataset.

Let’s say we want to get the most expensive property sold in 2025. We could write this query:

1SELECT max(price)

2FROM uk_price_paid

3WHERE toYear(date) = 2025;

┌─max(price)─┐

│ 127700000 │ -- 127.70 million

└────────────┘

But what about if we want to get the town corresponding to the maximum price. We can use the argMax function to do this:

1SELECT argMax(town, price)

2FROM uk_price_paid

3WHERE toYear(date) = 2025;

┌─argMax(town, price)─┐

│ PURFLEET-ON-THAMES │

└─────────────────────┘

The argAndMax function lets us get the town as well as the corresponding maximum price:

1SELECT argAndMax(town, price)

2FROM uk_price_paid

3WHERE toYear(date) = 2025;

┌─argAndMax(town, price)───────────┐

│ ('PURFLEET-ON-THAMES',127700000) │

└──────────────────────────────────┘

We can do the same with argAndMin to find the town and corresponding minimum price:

1SELECT argAndMin(town, price)

2FROM uk_price_paid

3WHERE toYear(date) = 2025;

┌─argAndMin(town, price)─┐

│ ('CAMBRIDGE',100) │

└────────────────────────┘

That looks like bad data, as it’s fairly unlikely that a property was sold for £100 in 2025.

Fractional LIMIT and OFFSET #

Contributed by Ahmed Gouda #

ClickHouse 25.11 also introduces fractional limit and offset. Using our same house prices dataset, we could write the following query to get the top 10% of counties based on average property price, by providing a limit of 0.1:

1SELECT county, round(avg(price), 0) AS price 2FROM uk_price_paid 3GROUP BY county 4ORDER BY price DESC 5LIMIT 0.1;

┌─county──────────────────────────────┬──price─┐

│ GREATER LONDON │ 431459 │

│ WINDSOR AND MAIDENHEAD │ 427476 │

│ WEST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE │ 417312 │

│ BOURNEMOUTH, CHRISTCHURCH AND POOLE │ 403415 │

│ SURREY │ 386667 │

│ BUCKINGHAMSHIRE │ 349638 │

│ CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE │ 343227 │

│ NORTH NORTHAMPTONSHIRE │ 338155 │

│ WOKINGHAM │ 332415 │

│ WEST BERKSHIRE │ 326481 │

│ BEDFORD │ 318778 │

│ OXFORDSHIRE │ 317245 │

│ HERTFORDSHIRE │ 317055 │

│ BATH AND NORTH EAST SOMERSET │ 304950 │

└─────────────────────────────────────┴────────┘

We can also specify a fractional offset. So if we wanted to get 10 of the counties based on average property price, but starting from the middle of the list, we can do this by providing an offset of 0.5:

1SELECT county, round(avg(price), 0) AS price 2FROM uk_price_paid 3GROUP BY county 4ORDER BY price DESC 5LIMIT 10 6OFFSET 0.5;

┌─county───────────────────┬──price─┐

│ TORBAY │ 170050 │

│ CITY OF NOTTINGHAM │ 169037 │

│ PEMBROKESHIRE │ 167116 │

│ WEST MIDLANDS │ 166271 │

│ LUTON │ 165885 │

│ NORTHUMBERLAND │ 164153 │

│ NORTHAMPTONSHIRE │ 164133 │

│ EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE │ 163334 │

│ ISLE OF ANGLESEY │ 162621 │

│ DERBYSHIRE │ 161320 │

└──────────────────────────┴────────┘

EXECUTE AS user #

Contributed by Shankar #

ClickHouse 25.11 also introduces EXECUTE AS <user>, which lets one user run queries on behalf of another user.

This functionality is helpful if an app authenticates as one user and performs tasks under other configured users for access rights, limits, settings, quotas, and audit purposes.

We can grant this power to a user by running the following query:

1GRANT IMPERSONATE ON user1 TO user2;

And then we can execute an individual query as someone else, like this:

1EXECUTE AS target_user

2SELECT * FROM table;

Or we can set those permissions for the whole session:

1EXECUTE AS target_user;

And then, every subsequent query will be run as target_user.