For most large-scale migrations, the primary bottleneck is the initial load, i.e., copying existing data across all tables from source Postgres to target Postgres.

While ongoing change data capture (CDC) keeps systems in sync before cutover, the initial copy of historical data often covers the majority of the overall migration timeline. For datasets measured in terabytes, this phase can take days, and in some cases, weeks, depending on the tool.

Let’s compare performance across pg_dump/pg_restore, native logical replication and PeerDB for initial load.

The benchmark setup was as follows:

- Source database: AWS RDS instance on Postgres 18 sized at db.r8g.2xlarge, 8 VCPUs, 64GB RAM, 12000 provisioned IOPS, gp3.

- Destination database: Postgres managed by ClickHouse on Postgres 18, 8 VCPUs, 64GB RAM, NVMe backed with 1875 GB storage. This was also in AWS.

- EC2: Sized at c5d.12xlarge, running ubuntu-noble-24.04-amd64

The above setup artifacts were all situated in the region us-west-2c.

The dataset we used is the firenibble database which consists of a table with a variety of types. The benchmark was conducted on a single large table, as this reflects most real-world schemas, which may contain hundreds of tables, but where one (or a few) large tables become the primary bottleneck during large database migrations.

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS firenibble

(

f0 BIGINT PRIMARY KEY GENERATED ALWAYS AS IDENTITY,

f1 BIGINT,

f2 BIGINT,

f3 INTEGER,

f4 DOUBLE PRECISION,

f5 DOUBLE PRECISION,

f6 DOUBLE PRECISION,

f7 DOUBLE PRECISION,

f8 VARCHAR COLLATE pg_catalog."default",

f9 VARCHAR COLLATE pg_catalog."default",

f10 DATE,

f11 DATE,

f12 DATE,

f13 VARCHAR COLLATE pg_catalog."default",

f14 VARCHAR COLLATE pg_catalog."default",

f15 VARCHAR COLLATE pg_catalog."default"

);

The tool used to create and populate this table is available in a public repository in PeerDB, you can check it out here. String lengths for population were set to 32. The table ended up being 1TB in size with 3.6 billion rows ingested.

tb_test=> select pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size('firenibble'));

pg_size_pretty

----------------

1000 GB

(1 row)

We performed the initial load for the above table to Postgres managed by ClickHouse with each of the three tools - PeerDB, pg_dump/pg_restore and native logical replication - separately.

pg_dump and pg_restore

Since we were working with a single table, we leveraged streaming between the dump and the restore here, looking like this:

time pg_dump

-d '<source_postgres_connection_string>'

-Fc

-t firenibble

--data-only

--verbose

| pg_restore

-d '<destination_postgres_connection_string>'

--data-only

--verbose

--no-owner

--no-acl

This allowed dumping and restoring simultaneously without waiting for one to finish. This also avoided the overhead of IOPS needed to dump to disk. The load was conducted with default compression settings for pg_dump.

While we’re here, we should mention that pg_dump and pg_restore do not offer parallelizing loads for a single table. We will take a look at how PeerDB achieves this later in this post.

pg_restore: connecting to database for restore

pg_restore: processing data for table "public.firenibble"

pg_restore: executing SEQUENCE SET firenibble_f0_seq

real 1024m58.739s

user 1133m6.474s

sys 39m19.008s

The full table was loaded at the destination after 17 hours 5 minutes.

The source RDS was the publisher, with a publication created with just this one table.

tb_test=> CREATE PUBLICATION fire_pub FOR TABLE firenibble;

CREATE PUBLICATION

From here, a subscription was created on Postgres managed by ClickHouse, pointing to the above database and publication.

logical_replication_test=# CREATE SUBSCRIPTION rds_subscription

logical_replication_test-# CONNECTION '<source_connection_string>'

logical_replication_test-# PUBLICATION fire_pub;

logical_replication_test=# NOTICE: created replication slot "rds_subscription" on publisher

logical_replication_test-# CREATE SUBSCRIPTION

This immediately begins the initial load. Note that here too parallel loading of a single table is not available; it’s done by a single synchronization worker in Postgres.

2026-02-17 21:34:27.175 UTC [35026:1] (0,521/2): host=,db=,user=,app=,client= LOG: logical replication table synchronization worker for subscription "rds_subscription", table "firenibble" has started

2026-02-18 06:15:18.842 UTC [35026:2] (0,521/8): host=,db=,user=,app=,client= LOG: logical replication table synchronization worker for subscription "rds_subscription", table "firenibble" has finished

All in all, native logical replication loaded the data in 8 hours 40 minutes.

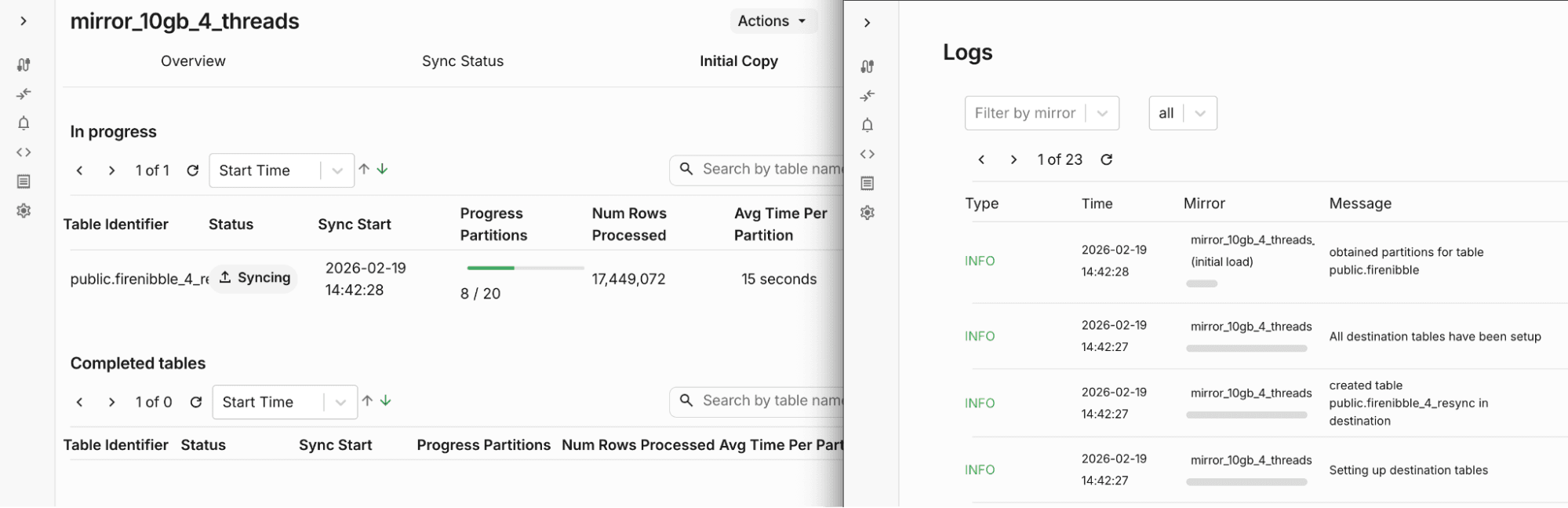

PeerDB’s architecture involves peers, which point to data stores, and mirrors, which are data movement pipelines between peers. Here, the source peer was RDS and the target peer was Postgres managed by ClickHouse.

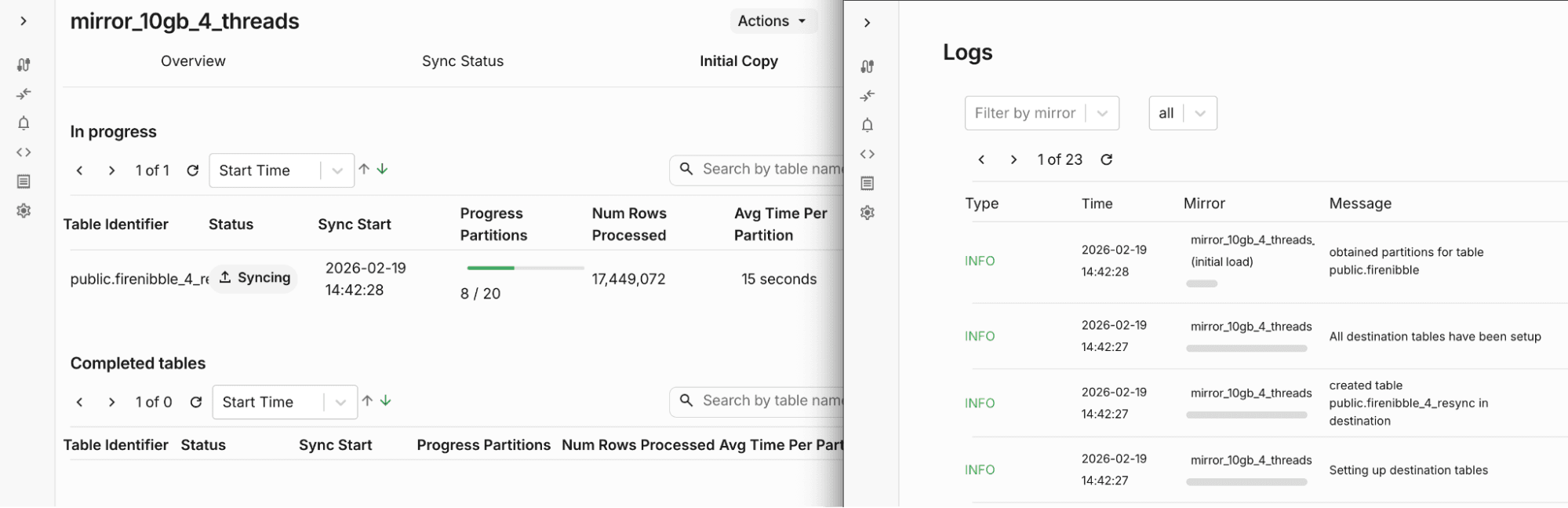

When creating a mirror in PeerDB, you can set a value for initial load parallelism as well as other parameters to determine size of logical partitions and parallelism across tables.

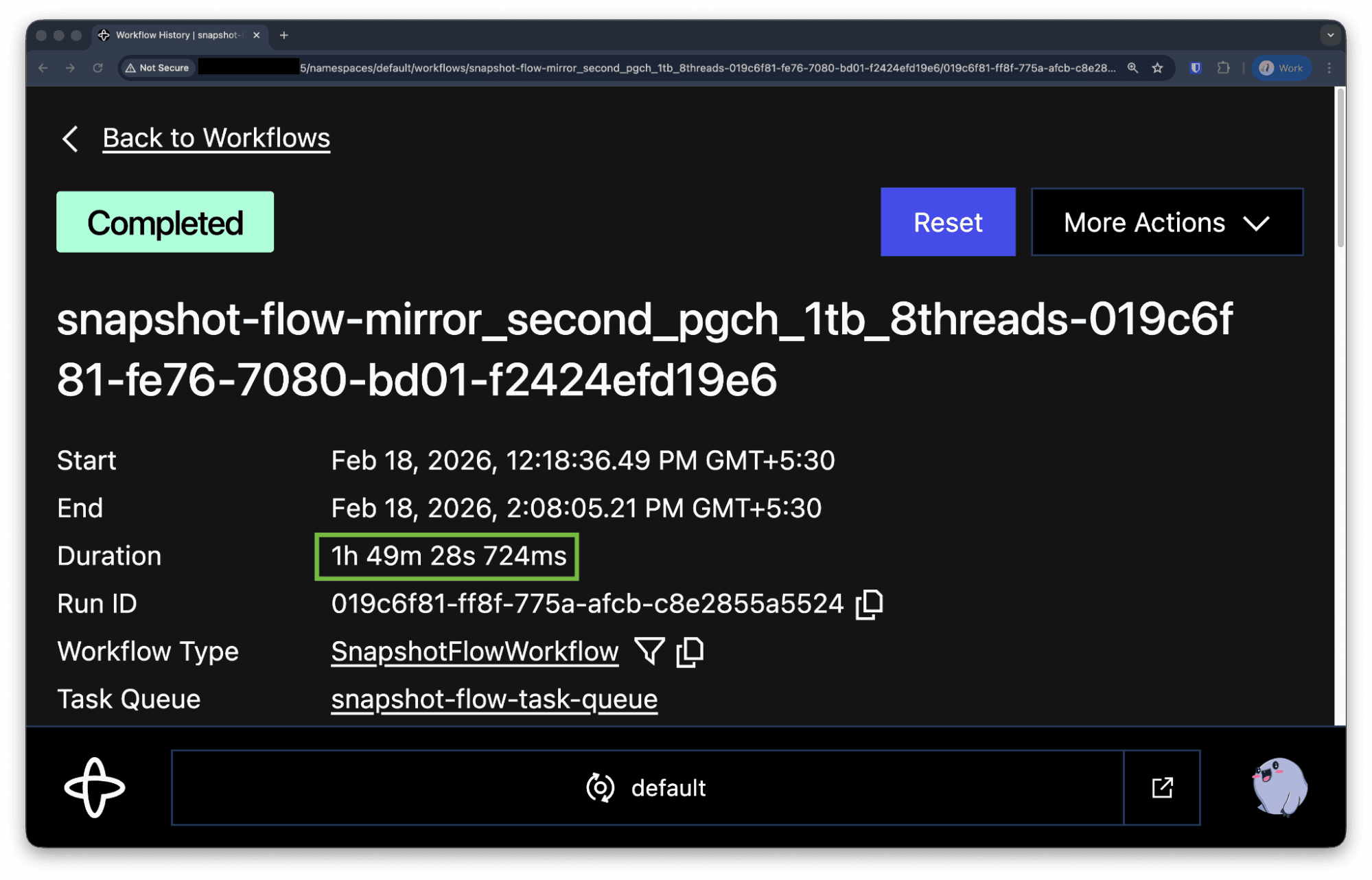

In our case, since we had 1 table, we had parallelism across tables set to 1, and per-table parallelism to be 8.

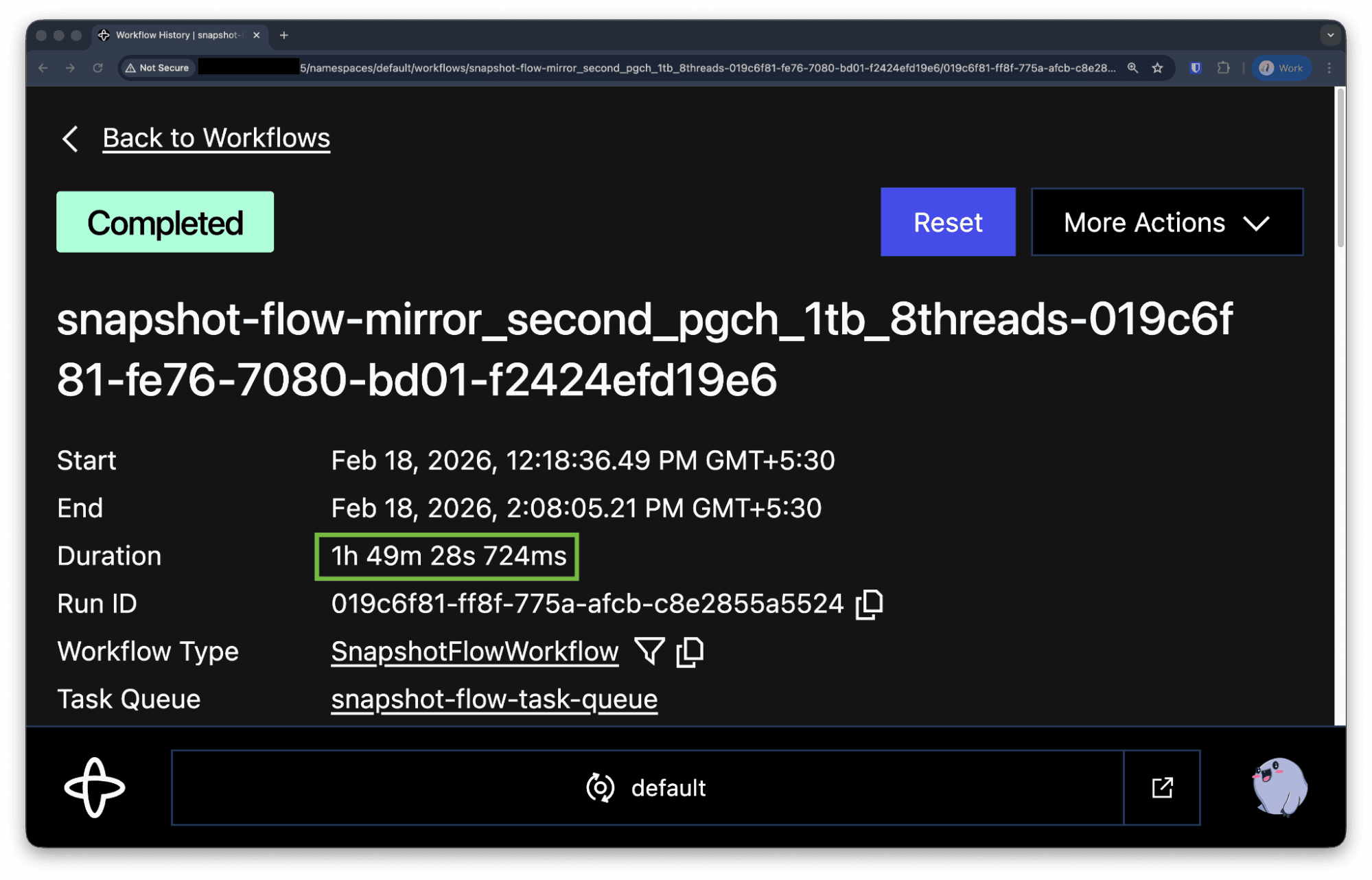

All in all, PeerDB synced the 1 TB table in 1 hour 49 minutes.

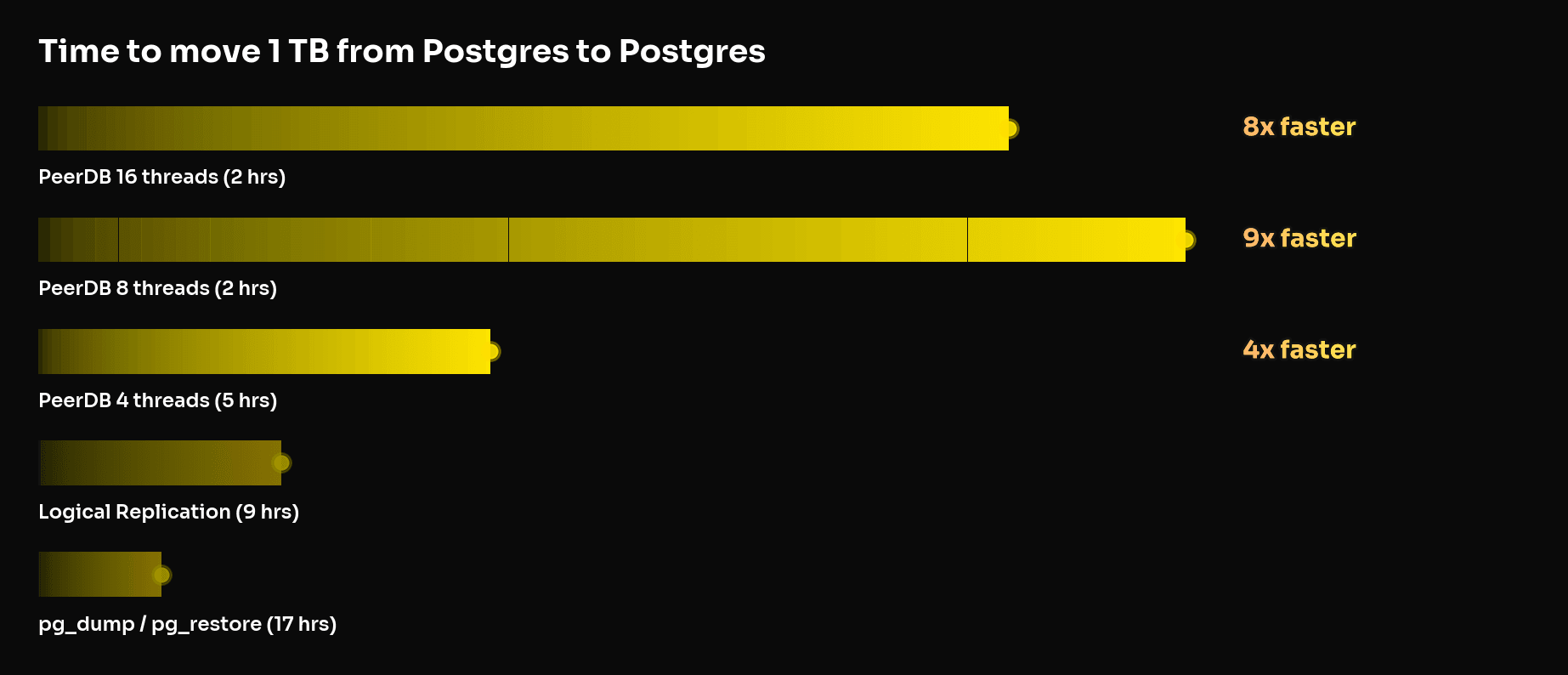

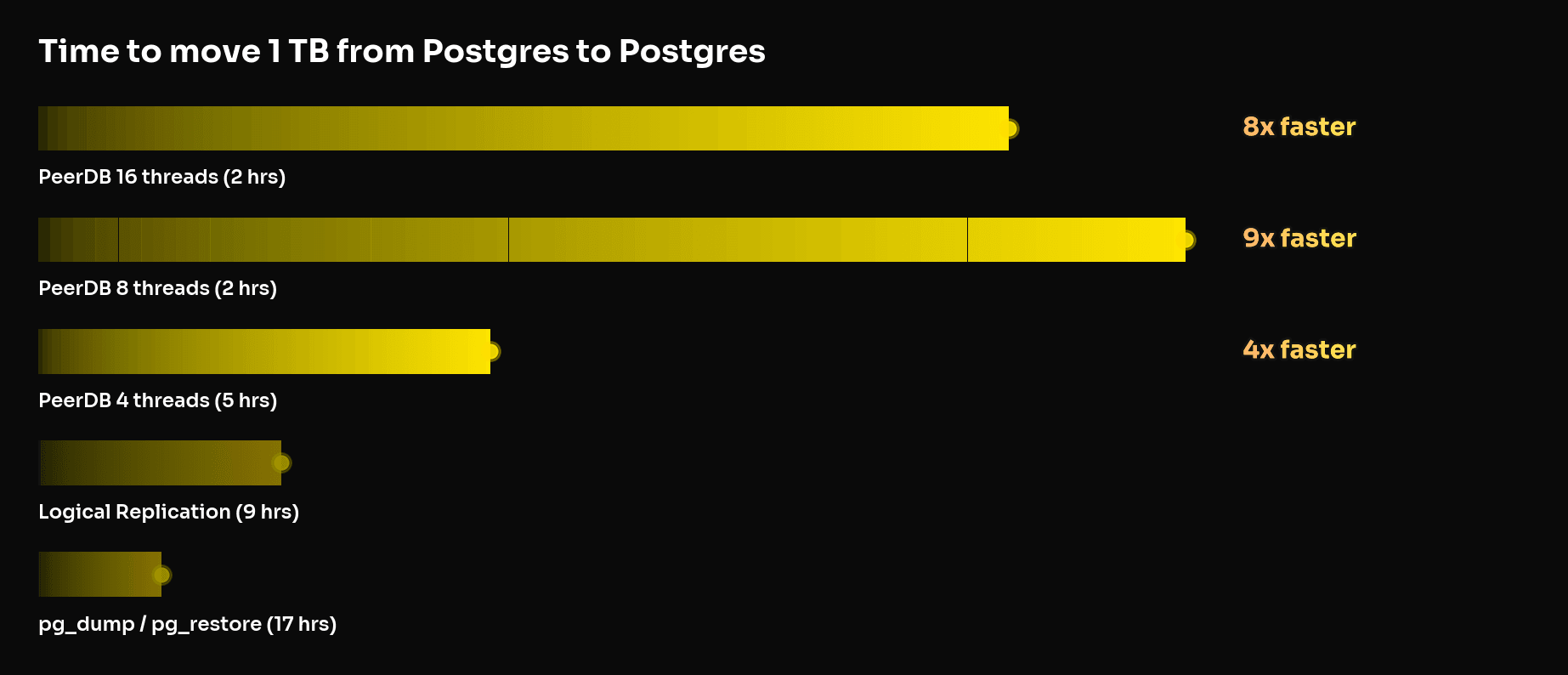

We ran initial load tests across different sizes of the above table and parallelism specs of PeerDB. The results are below.

| 10 GB | 100 GB | 1000 GB |

|---|

| pg_dump / pg_restore | 11 minutes 20 seconds | 1 hour 48 minutes | 17 hours 5 minutes |

| Native logical replication | 2 minutes 43 seconds | 23 minutes 33 seconds | 8 hours 40 minutes |

| PeerDB with 4 threads | 1 minute 26 seconds | 18 minutes 45 seconds | 4 hours 39 minutes |

| PeerDB with 8 threads | 1 minute 25 seconds | 15 minutes 24 seconds | 1 hour 50 minutes |

| PeerDB with 16 threads | 1 minute 25 seconds | 10 minutes 34 seconds | 2 hours 10 minutes |

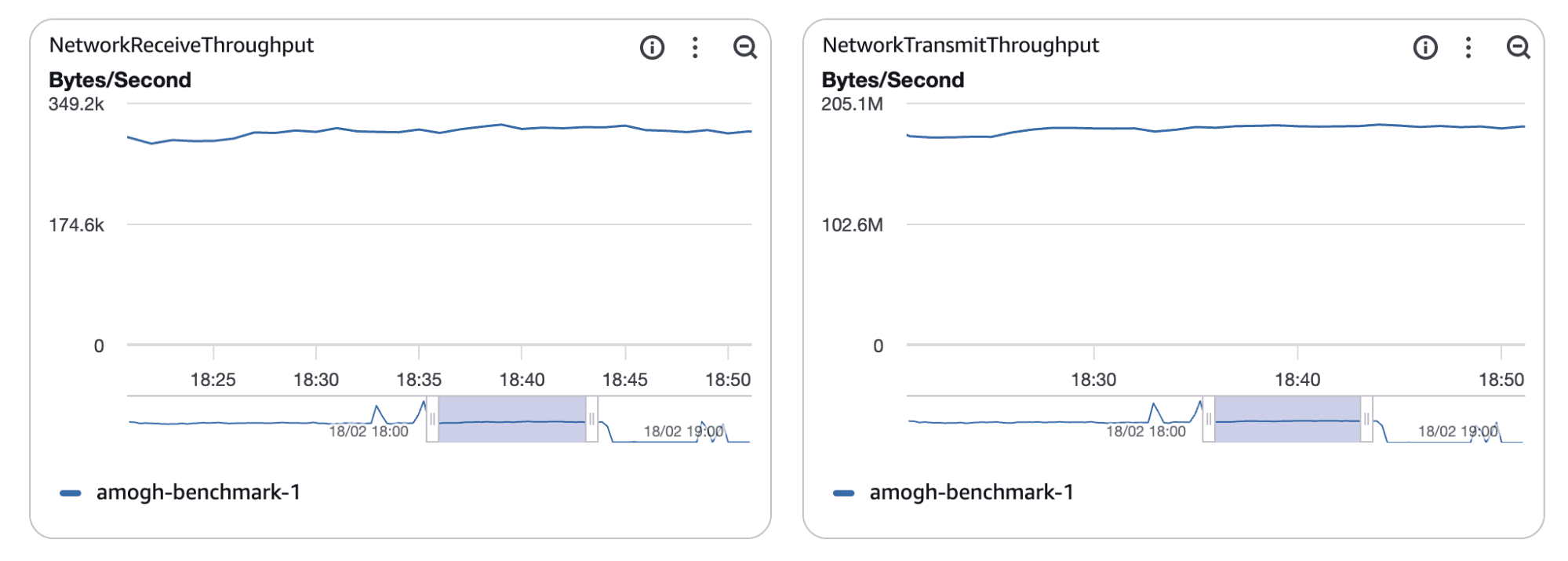

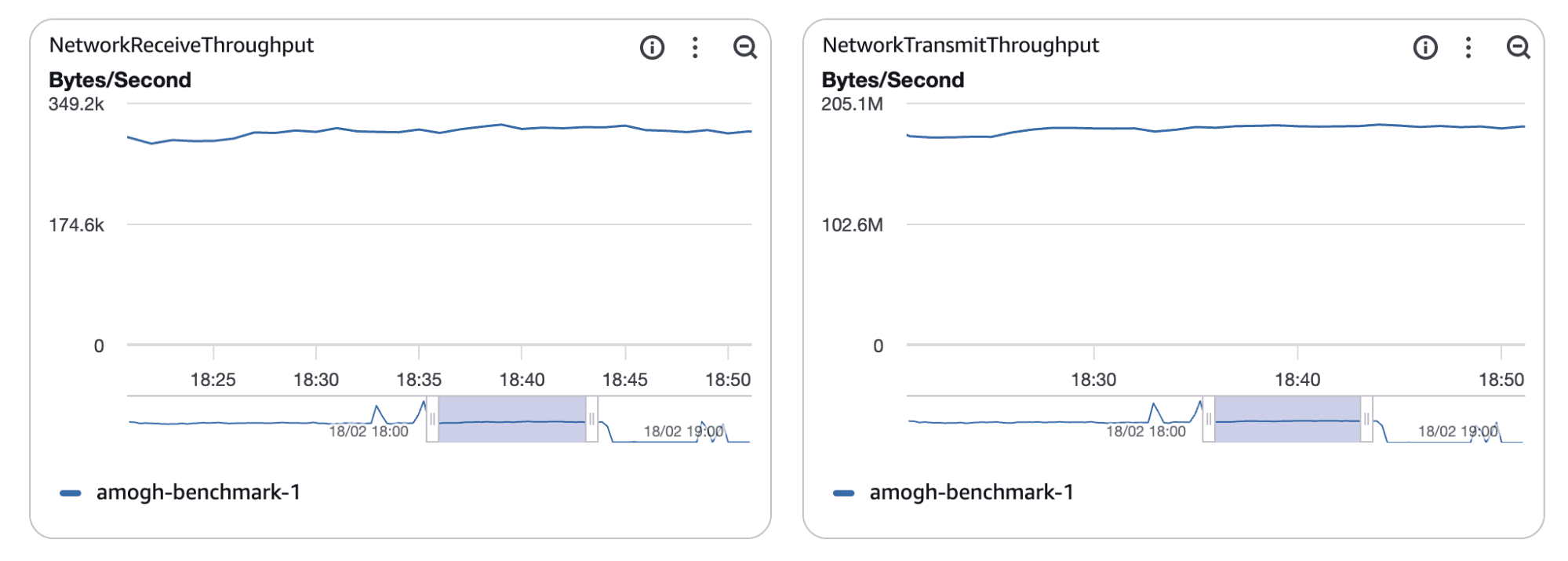

The results show an interesting pattern where beyond a certain threshold of parallelism for a given data size, the workload hits the limits of the network bandwidth envelope for the RDS instance and increase in parallel threads no longer give huge gains in performance.

Plateaus in network throughputs on the source

Plateaus in network throughputs on the source

Across the matrix, the relative performance of PeerDB looks as follows.

Why is PeerDB faster than pg_dump/pg_restore and native logical replication?

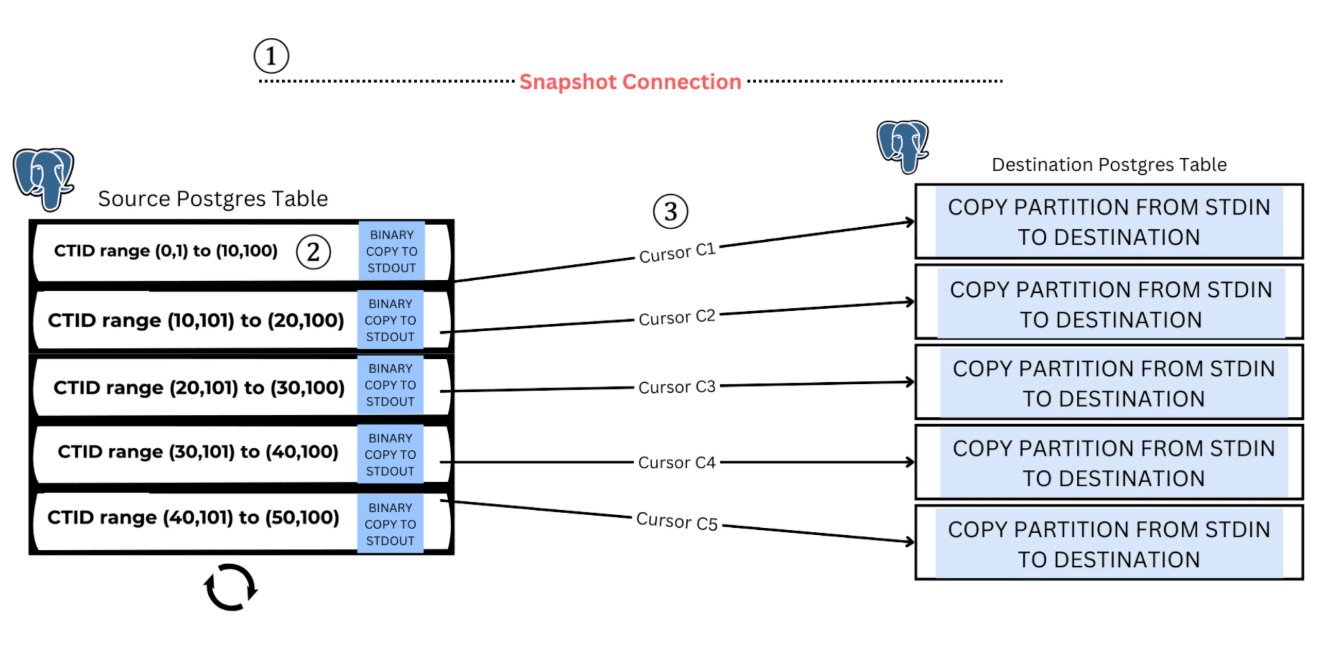

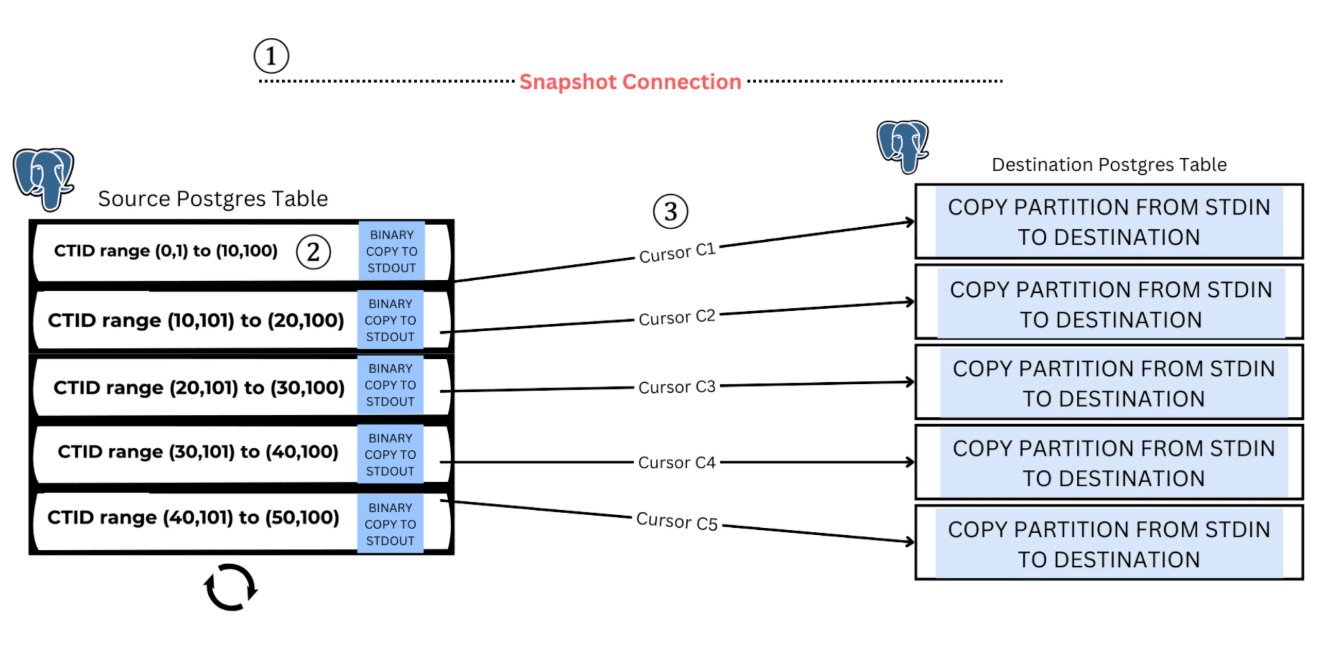

The performance gains observed in our benchmarks stem directly from how PeerDB performs the initial load. Parallel Snapshotting in PeerDB enables parallelization of the initial load for a single large table by logically partitioning it based on CTID. This approach preserves a consistent snapshot while streaming the partitions concurrently, significantly reducing load time compared to a single-threaded full-table scan. Let's look at how this works:

The process begins by creating a consistent snapshot of the source database using pg_export_snapshot(). This ensures that all parallel threads read from the same point in the database in time.

CTID is a system column per table that represents the physical location of a row inside a table in Postgres.

The table is divided into multiple logical segments using CTIDs. By splitting the table into CTID ranges, we create independent chunks of data.

Each worker then reads one CTID range at a time using a SELECT query restricted to that range and streams the results to the destination.

Queries that filter by CTID ranges are efficient because they operate directly on the physical row locations inside the table. In practice, this allows the database to read rows in the order they are stored on disk. Reading data in storage order improves I/O performance and avoids repeatedly scanning the same parts of the table.

In older versions of Postgres, TID range scans are not supported. In these scenarios, PeerDB also offers two other partitioning strategies – MinMax and NTILE - but these are not in the scope of this post.

Each logical partition created above is transferred using PostgreSQL’s binary COPY protocol:

COPY TO STDOUT on the sourceCOPY FROM STDIN on the target

This allows dumping and restoring to happen at the same time, without writing to intermediate files. The binary format also reduces overhead compared to text-based ones, as will be explained more in detail later.

To avoid using excessive memory, each worker uses cursors to fetch and stream data in batches.

Resiliency and observability

A pain point when dealing with single, sequential loads when using tools like pg_dump or native logical replication is a lack of granular visibility into initial load’s progress. This is a benefit with PeerDB’s parallel initial load where you can see exactly how many partitions are synced, and how many remain. This allows you to estimate initial load times easier.

Another pitfall with single partition dumps is the risk of a failure at some point, causing potentially days or weeks of progress to be lost. PeerDB has automatic failure retry mechanisms surrounding every activity it performs. With parallel snapshotting, intermittent errors such as network cuts will impact just that single partition, resulting in an instant retry with negligible impact to the overall initial load time.

To reduce migration overhead we don’t just think about parallelism. We also eliminate unnecessary data transformations during transfer or after.

PostgreSQL's wire protocol supports two formats for transmitting data between client and server. The first one is the text format, where data is encoded as human-readable strings. This requires parsing on the receiving end, and has network overhead due to ASCII encoding.

PeerDB uses the binary format, where data is encoded in Postgres' native binary representation. Through this, we do not need to parse information and pass through the data type information to the target, ensuring we create target tables with the exact same data type specifications for every column as on source.

This can be felt strongest when dealing with complex data types such as JSON arrays. When receiving such data in text format, unmarshalling JSON values can cause loss in precision, lack of support for constants such as NaNs or INFs, as well as a hit to sync performance. When dealing in the binary format, no such transformations are necessary.

Preserving data in its native binary representation minimizes the risk of type mismatches or precision issues, ensuring a predictable and seamless cutover when application traffic switches to the target.

Efficient and reliable CDC

Once the initial snapshot is complete, the system transitions to continuous change data capture (CDC) to keep the source and target in sync until cutover. This phase is critical for minimizing downtime and maintaining consistency under ongoing write load.

In this section, we’ll look at two key engineering considerations: efficient replication slot consumption and reducing replication overhead, particularly for large or complex row structures.

Consuming the replication slot is crucial when it comes to sustaining high-throughput ingestion workloads, where falling behind in replication lag can be detrimental to the source Postgres instance’s storage due to a heavy slot – which can only be recovered from via a full resync via dropping the slot.

PeerDB reuses a single replication connection across its sync batches, ensuring the replication slot is always active. It includes periodic sending of status standby updates to Postgres to avoid replication timeouts being hit.

It is also architected in a way where pulling data from source and pushing data to destination are independent processes, so failures on the push side will not hinder slot consumption.

PeerDB offers replication slot lag alerting features out of the box via Slack and Email, ensuring that there is no scope for outages or surprises for your business workloads.

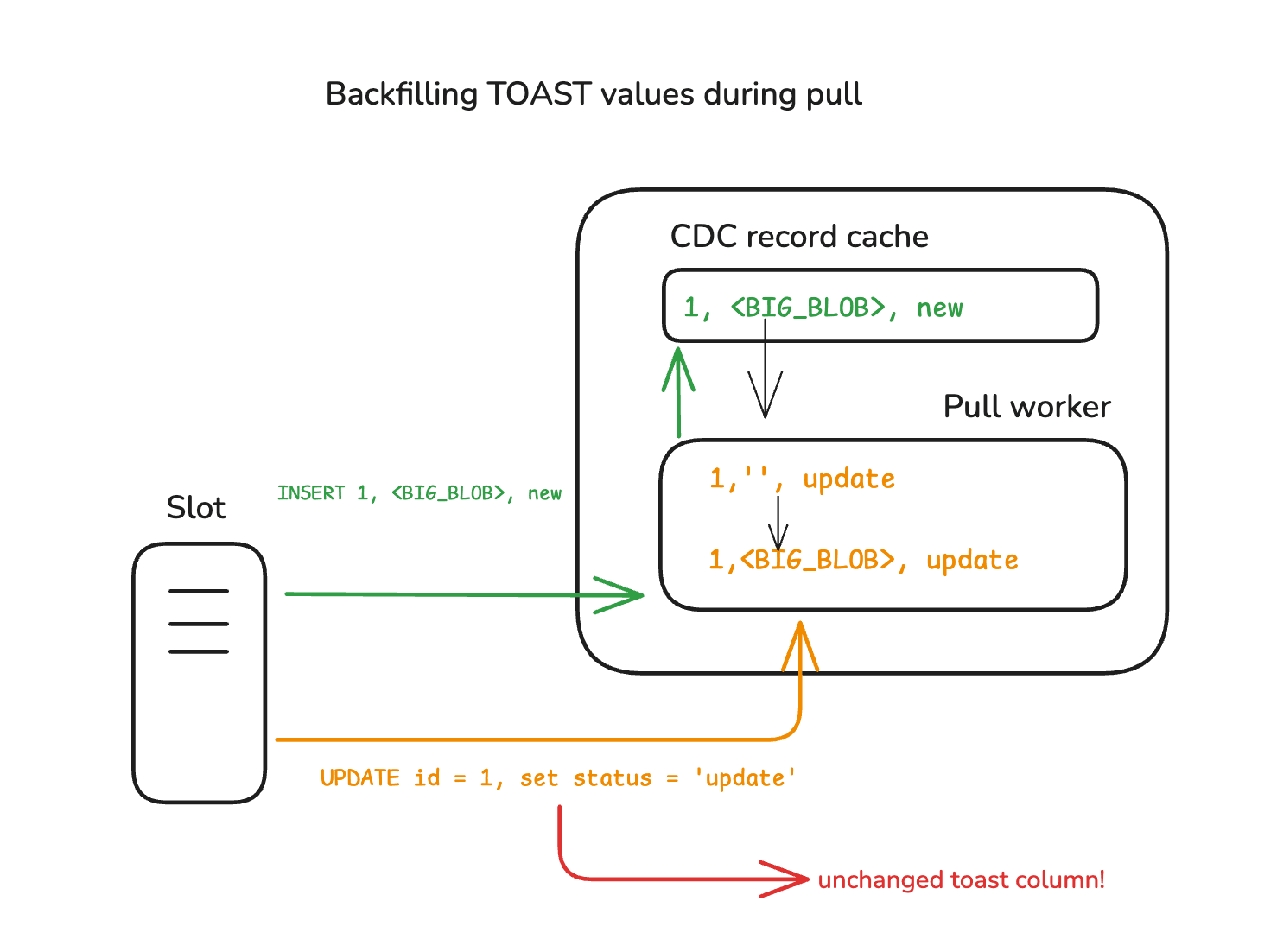

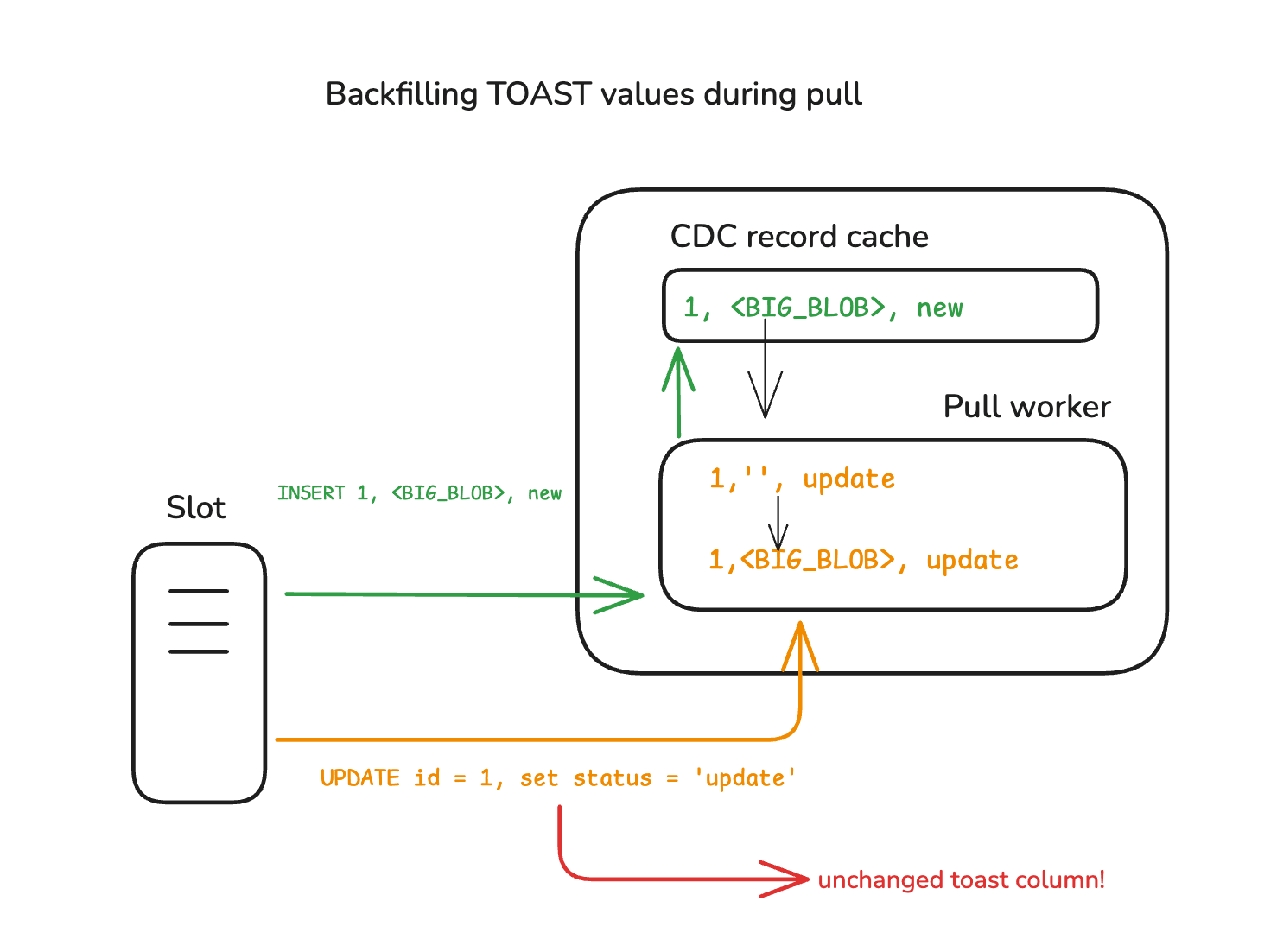

Support for unchanged TOAST columns

TOAST is PostgreSQL's mechanism for handling large field values. During Change Data Capture (CDC) using Postgres’ default logical decoding plugin - pgoutput - unchanged TOAST columns aren't included in the replication stream and appear as NULL values, which can be problematic during data migration. This is one of the common pitfalls of logical decoding users.This can be addressed by setting REPLICA IDENTITY FULL on the source tables. However, this is often a concern for users as it requires modifying the source database.

PeerDB supports streaming of unchanged TOAST columns during CDC without having to set REPLICA IDENTITY FULL to source tables. In summary, it relies on the previously stored values of the TOAST columns in the target to reconstruct unchanged TOAST columns.

Let’s take a closer look at the internal algorithm.

When reading logical replication messages from Postgres, PeerDB maintains a cache of CDC records scoped to the current batch of records.

UPDATEs with unchanged TOAST columns are detected using information provided via Postgres’ logical replication protocol for messages. PeerDB is then able to look up these columns present in earlier INSERT or UPDATE records in the same batch, and backfill the missing values.

Using MERGE to retrieve previous state of the TOAST column

PeerDB stores all pulled change data in a raw table. As part of this effort, we store in the raw table all unique combinations of TOAST columns for each table in the batch.

Postgres’ MERGE command is then used to replicate insert, update and delete records from the raw table to the target table, making sure to keep unchanged TOAST column values intact in the destination table.

We can walk through a simple example MERGE command for the above diagram’s table schema.

- First, we group records by their primary key value, and rank them based on when they were pulled from source.

WITH src_rank AS (

SELECT

_peerdb_data,

_peerdb_record_type,

_peerdb_unchanged_toast_columns,

RANK() OVER (

PARTITION BY (_peerdb_data ->> 'id') :: integer

ORDER BY

_peerdb_timestamp DESC

) AS _peerdb_rank

FROM

peerdb_temp._peerdb_raw_my_mirror

WHERE

_peerdb_batch_id = $ 1

AND _peerdb_destination_table_name = $ 2

)

- Now, we issue a

MERGE command to push each change-data to the final table.

MERGE INTO "public"."my_table" dst USING (

SELECT

(_peerdb_data ->> 'id') AS "id",

(_peerdb_data ->> 'blob') AS "blob",

(_peerdb_data ->> 'status') AS "status",

_peerdb_record_type,

_peerdb_unchanged_toast_columns

FROM

src_rank

WHERE

_peerdb_rank = 1

) src ON src."id" = dst."id"

- First, we must account for inserts, which is straightforward.

WHEN NOT MATCHED THEN

INSERT

("id", "blob", "status", "_peerdb_synced_at")

VALUES

(

src."id",

src."blob",

src."status",

CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

)

- Now, we get into the conflict handling strategy in the case of updates. In an update record,

_peerdb_unchanged_toast_columns is a comma-separated string list of column names whose values are unchanged. If there are no such values, it will be an empty string like so.

WHEN MATCHED

AND src._peerdb_record_type != 2

AND _peerdb_unchanged_toast_columns = ''

THEN

UPDATE

SET

"id" = src."id",

"blob" = src."blob",

"status" = src."status",

"_peerdb_synced_at" = CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

- In the case above though, for instance,

blob was unchanged in the update. That would then be handled like:

WHEN MATCHED

AND src._peerdb_record_type != 2

AND _peerdb_unchanged_toast_columns = 'blob'

THEN

UPDATE

SET

"id" = src."id",

"status" = src."status",

"_peerdb_synced_at" = CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

WHEN MATCHED

AND src._peerdb_record_type = 2 THEN DELETE

A look ahead and getting started

At ClickHouse, we’re actively working on making Postgres migrations a one-click experience. This is a first step in that direction. Stay tuned for more updates in the near future!

PeerDB can be set up with a single command. You can head over to our open-source repository on GitHub to get started. Once ready, create a Postgres to Postgres by ClickHouse mirror with a few clicks by following our documented guides.

In the meantime, if you’d like to explore this firsthand, sign up for the Postgres managed by ClickHouse private preview and launch a high-speed OLTP stack in minutes with the help of our quickstart.