In our CI/CD system at ClickHouse we use lambda functions a lot. AWS provides two ways to deploy a lambda function: Docker images and ZIP archives.

The latter is much lighter, so we have used it exclusively since November 2022. Besides the artifact size, it was easier to automate it in a simple script.

In late 2023, we started using Terraform/OpenTofu to manage the CI/CD infrastructure. This raised the question of "how should we manage artifacts to deploy?"

The question contains two different points:

-

The artifact should not change the content after each rebuild; otherwise, it would be redeployed on each execution of the

tofu applycommand. -

Ideally, it should be built on the fly, without any additional infrastructure on top, like pushing it to S3 or so

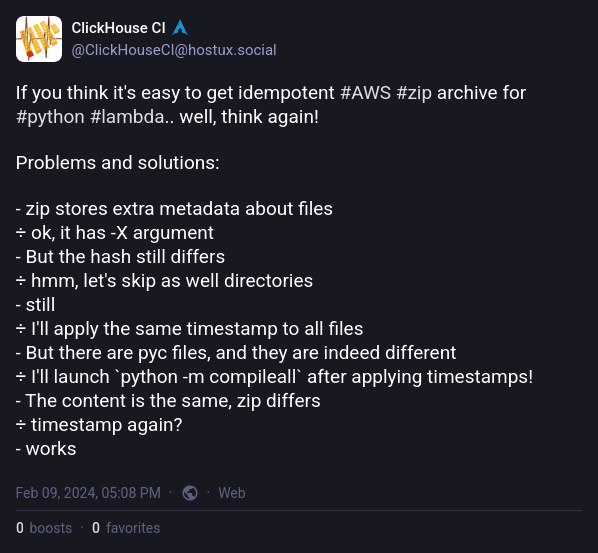

Building metadata-independent ZIP archive on linux #

Challenge one: the order matters #

There are many factors affecting the ZIP archive content. One of the unexpected (for me) things is the order of archived files. Here's the example:

# create files 1 2 3 4 5

$ touch {1..5}

# archive them in sorted and reserved order

$ ls [1-5] | sort | zip -q -0 --names-stdin sorted.zip

$ ls [1-5] | sort -r | zip -q -0 --names-stdin reversed.zip

# compare two files byte-by-byte

$ cmp -l sort.zip rev.zip

31 61 65

62 62 64

124 64 62

155 65 61

202 61 65

249 62 64

343 64 62

390 65 61

And here's the very first issue to solve. The order of files must be the same.

Besides that, we should omit passing the directories to the zip command. Otherwise, it could cause inconsistency. The argument -D helps here.

So, here's the very first solved issue.

export LC_ALL=c

# zip uses random files order by default, so we sort the files alphabetically

find . ! -type d -print0 | sort -z | tr '\0' '\n' | zip -XD -0 ../"$PACKAGE".zip --names-stdin

The found files are null-divided and sorted, and then null is replaced by a new line and passed to the ZIP.

Challenge two: age matters #

This is the part of the man zip about one of the arguments above:

-X

--no-extra

Do not save extra file attributes (Extended Attributes on OS/2,

uid/gid and file times on Unix). The zip format uses extra

fields to include additional information for each entry. Some

extra fields are specific to particular systems while others

are applicable to all systems. Normally when zip reads entries

from an existing archive, it reads the extra fields it knows,

strips the rest, and adds the extra fields applicable to that

system. With -X, zip strips all old fields and only includes

the Unicode and Zip64 extra fields (currently these two extra

fields cannot be disabled).

So, it should ignore timestamps.. But!

$ touch -t 201212121212 {1..5}

$ zip -XD0q older.zip {1..5}

$ touch -t 201212121213 {1..5}

$ zip -XD0q newer.zip {1..5}

$ cmp -l older.zip newer.zip

11 200 240

42 200 240

73 200 240

104 200 240

135 200 240

168 200 240

215 200 240

262 200 240

309 200 240

356 200 240

Somebody lies. So, before archiving the files, we need to change the last modification time.

find "$PACKAGE" ! -type d -exec touch -t 201212121212 {} +

Challenge three: Python byte-code #

According to the recommendations, including .pyc files in the lambda archive speeds-up the cold start of the lambdas, but can cause issues with the byte-code version. The byte-code version depends on the Python version and the system architecture.

After some experiments, we found that the best way to skip the .pyc files is to use the -x,--exclude option of the zip command.

Final challenge: the OS matters #

The last challenge is the OS. The ZIP archive format depends on the OS on which it was created. MacOS and Linux produce different ZIP archives, even if the content is the same. At this point we were already too tired of finding out what was going on. It was clear that any difference in zip binary could cause a bit-difference in the archives.

The best way we came up with is using Python to create the ZIP archive. Python's zipfile module creates a consistent ZIP archive, regardless of the OS. But to be completely sure, we use Python from the public.ecr.aws/lambda/python image, which is the same as the one used by AWS Lambda.

docker_cmd=(

docker run -i --net=host --rm --user="${UID}" -e HOME=/tmp --entrypoint=/bin/bash

--volume="${WORKDIR}/..:/ci" --workdir="/ci/${DIR_NAME}" "${DOCKER_IMAGE}"

)

"${docker_cmd[@]}" -ex <<EOF

cd '$PACKAGE'

find ! -type d -exec touch -t 201212121212 {} +

python <<'EOP'

import zipfile

import os

files_path = []

for root, _, files in os.walk('.'):

files_path.extend(os.path.join(root, file) for file in files)

# persistent file order

files_path.sort()

with zipfile.ZipFile('../$PACKAGE.zip', 'w') as zf:

for file in files_path:

zf.write(file)

EOP

EOF

Building the virtual environment for the lambda #

The code to address this challenge is quite simple. The only thing to remember is that the virtual environment should be created with the same Python version as the one used by AWS Lambda.

docker_cmd=(

docker run -i --net=host --rm --user="${UID}" -e HOME=/tmp --entrypoint=/bin/bash

--volume="${WORKDIR}/..:/ci" --workdir="/ci/${DIR_NAME}" "${DOCKER_IMAGE}"

)

rm -rf "$PACKAGE" "$PACKAGE".zip

mkdir "$PACKAGE"

cp app.py "$PACKAGE"

if [ -f requirements.txt ]; then

VENV=lambda-venv

rm -rf "$VENV"

"${docker_cmd[@]}" -ex <<EOF

'$PY_EXEC' -m venv '$VENV' &&

source '$VENV/bin/activate' &&

pip install -r requirements.txt &&

# To have consistent pyc files

find '$VENV/lib' -name '*.pyc' -delete

cp -rT '$VENV/lib/$PY_EXEC/site-packages/' '$PACKAGE'

rm -r '$PACKAGE'/{pip,pip-*,setuptools,setuptools-*}

chmod 0777 -R '$PACKAGE'

EOF

fi

Here we check if the lambda function has a requirements.txt file. If it does, we create a virtual environment with the same Python version as the one used by AWS Lambda, install the dependencies, and copy the site-packages to the lambda package directory. To remove the unnecessary files, we delete the pip and setuptools directories as well as Python byte-code files.

Conclusion #

The full script doing the job is available here. Later it was moved into the private repository, but it is still used in Terraform/OpenTofu configuration to deploy the lambda functions.